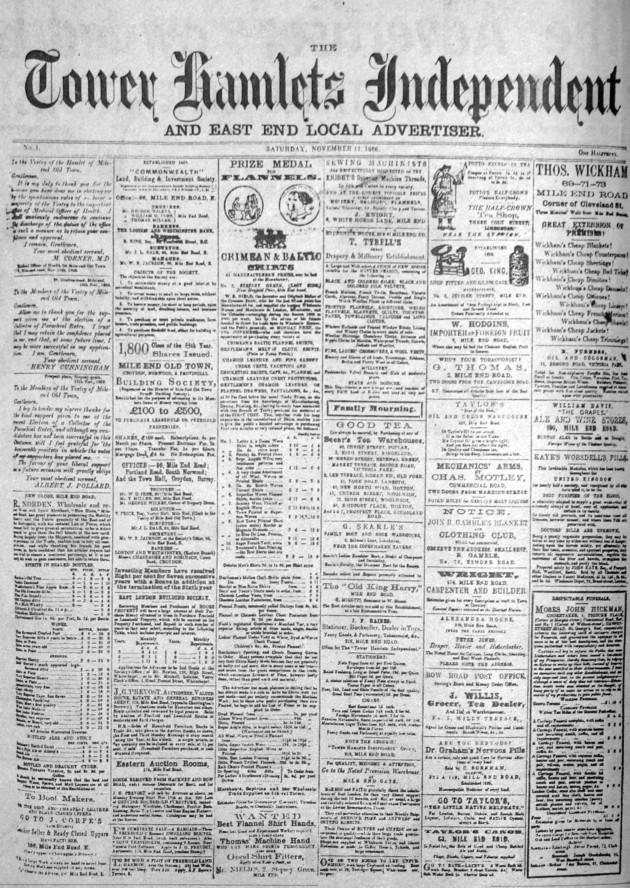

The second of our series on the 150 years we’ve been reporting since our first edition on Saturday, November 17, 1866, looks at the arrival of William Booth’s Salvation Army mission to clean up the “vile and wicked” East End of London, a mission that is met with typical violent opposition from an ‘army of skeletons’. Advertiser contributor Michael Simmons has a special connection to the East End’s infamous ‘Opposition Skeleton Army’ doing battle with Booth’s Salvationists...

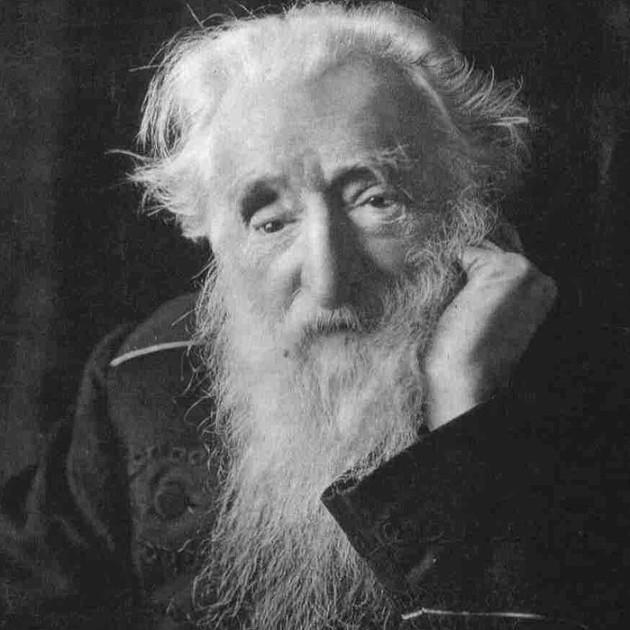

1866: William Booth has been preaching for just a year amid street criminals in a breeding ground for “the vile and the wicked”, where prostitution, poverty, drunkenness and debauchery are rife, writes Michael Simmons.

He arrives in the East End of London on his evangelical “military” campaign to rescue the poor the year before the Tower Hamlets Independent & Local Weekly Advertiser’s appearance.

It’s a struggle for Booth who is barred from using church or chapel buildings because his movement attracts violence. The police refuse to let him hold evangelical meetings in public parks, so he borrows a dancing school hall, a theatre, even a pub, or sometimes making do with a borrowed shed, stable or a skittle alley.

Booth acquires the use of a patch of green in Whitechapel, next to an old Quaker burial ground at Vallance Road, to erect a large tent for 300 people at a time.

He sets up his HQ in a terraced house in Cannon Street Road as the East End becomes the new Salvation Army’s main battleground.

The Salvationists are often attacked by an opposition ‘Skeleton Army’ funded by tavern keepers worried about losing their trade to the temperance preachers.

The Advertiser’s forerunner, the Bethnal Green Post, reports: “A rabble of pure and unadulterated ‘roughs’ has been infesting the district for weeks. These vagabonds style themselves the ‘Skeleton Army’ with their own collectors with shopkeepers, publicans, beer-sellers and butchers subscribing.

“They are the most consummate loafers and unmitigated blackguards, worthy of the disreputable class of publicans who hate the London School Board, education and temperance and who, seeing the beginning of the end of their immoral traffic, are prepared for the most desperate enterprise.”

Charles Jeffries emerges from the slums of Shadwell and Ratcliff, growing up in poverty, the son of a rigger put out of work by the mechanising of the docks.

The youth is on the streets drinking, sleeping rough and living on his wits and petty theft, drifting from job to job.

He and his gang set out to do battle with Booth’s “soldiers”—wearing distinctive clothing, marching and carrying Skull & Crossbones flags, hurling refuse and abuse at Booth’s Salvationists.

The efforts to break up the Salvation Army are carried out in the most shameless fashion, with 669 assaulted in one year. Mobs attack Salvationists while police arrest them and magistrates sentence them—86 are actually thrown into prison!

Jeffries is partial to the rough life and enjoys street battles and picking fights, even going to Salvationist meetings for a good scrap. He enjoys being turned out of the tent in Vallance Road for creating a disturbance—better than the circus, he says.

But everything changes just before his 18th birthday. The petty criminal who prefers thieving, fighting and drinking suddenly finds a new path in life on New Year’s Eve, 1881, outside the Blind Beggar pub in the Whitechapel Road, where a Salvation Army procession has just passed.

Jeffries and his Skeleton Army follow the Salvationists to their meeting hall and sit in the front row.

They are joined by a young mother with her one-year-old son who she plants on the knee of one of the ‘Skeletons’. The child is then passed along the line, the ‘Skeletons’ being so preoccupied that they remain quiet.

Suddenly Jeffries and some of his mates make their way forward and are soon kneeling. The audience rises, fearing a practical joke. Salvationists rush forward to turn the ‘Skeletons’ out, only to be told by Booth to kneel with them. They spend the night in prayer.

“Between 20 and 30 souls were the result of this wonderful night’s fight…”

Charles Jeffries, my grandfather, is one of the 30, who goes on to a distinguished Salvation Army career after his conversion, working as a missionary.

He dies in 1936 in Florida. Memorial services are held in Florida, New York and London. Traffic is brought to a standstill in central London when a service is held at the Salvation Army hall in Oxford Street.

Charles Jeffries had travelled a long road from Skeleton to Salvationist.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here