A veteran of 102 sat in her wheelchair beneath the new memorial in Bethnal Green Gardens being unveiled with her memories of the 173 people who died in Britain’s worst wartime civilian disaster.

Retired doctor Joan Martin was on duty in the A&E department at the Children’s Hospital in Hackney Road the night the injured were brought in from the air-raid shelter and bodies of those crushed to death in the rush to reach safety.

She was the oldest of the veterans at yesterday’s unveiling in Bethnal Green Gardens who included survivors of the infamous stairway crush and families of those who died on that fateful night of March 3, 1943.

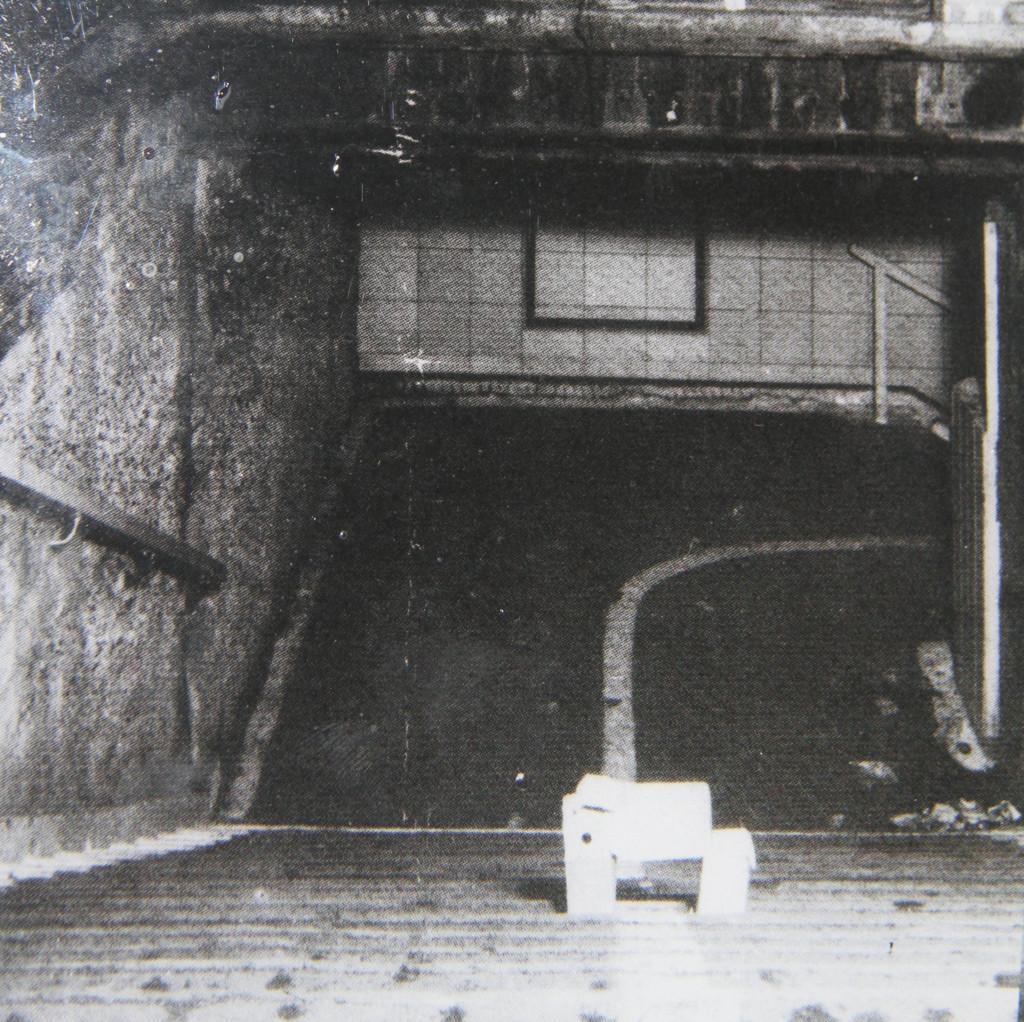

Crowds trying to reach safety during a false air-raid alert squeezed into the narrow and badly-lit staircase down to the underground shelter which had no safety railings and were crushed by the surge.

Previous warnings by Bethnal Green Council about inadequate safety had gone unheeded by the Civil Defence authorities—facts hidden from the public until 34 years after the 173 men, women and children had paid the price with their lives.

The Rector of Bethnal Green, Fr Alan Green, blessed the Stairway to Heaven memorial erected a few feet from the original stairs which are now the entrance to the Underground station as spectators and veterans like Dr Martin paid a minute’s silence in the cold and drizzle.

“The names of those who died were hidden away for 34 years after the war,” he told the crowd.

“Their names are now permanently and openly publicised, so that future generations should be inspired to work for peace.”

The unveiling of the £600,000 marble and teak memorial was the result of 10 years’ fundraising by the Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust.

The campaign got an early boost a decade ago through two women among yesterday’s guests, former Tower Hamlets civic mayor Anne Jackson who made the memorial her ‘charity of the year’ in 2007 and Cllr Denise Jones who was council leader that year.

They are among the sympathizers who now want to see an official government apology to the people of Bethnal Green wrongly blamed in 1943 for panic.

Cllr Jones told the East London Advertiser: “An apology like the Hillsborough disaster is a good idea. Today’s government shouldn’t be blamed, but could give an apology because it’s time.”

This sentiment and criticism of the government cover-up by wartime Home Secretary Herbert Morrison were echoed by political figures at yesterday’s unveiling.

Tower Hamlets mayor John Biggs told the paper: “The cover-up to maintain public morale was a misrepresentation.

“There was no reason why it was kept under wraps for the next 34 years.”

Bethnal Green’s MP Rushanara Ali spoke of the blame that followed in the aftermath when survivors and victims’ families faced “double tragedy of losing loved ones, then being blamed for it”.

She added: “That’s just not right—they didn’t get justice at Bethnal Green.

“Evidence shows that people should not have been blamed in that way. It was wrong. “People here in the East End suffered, during the war more than any other part of the country—the Blitz even began here.”

Three veterans including Dr Martin waiting beneath the memorial then cut the ribbon to formally unveil the Stairway to Heaven plinth.

She was joined by the youngest survivor, Margaret McKay, now 75, a six-month-old baby whose mother perished on the stairs, and Alf Morris, 88, who was rescued at the age of 13 from the crush by ARP air-raid warden Maud Chumdley.

Margaret was rescued from the arms of her mum Ellen Ridgeway who screamed out for rescuers to save her baby as she was being crushed to death.

“My mum was suffocating on the stairs,” Margaret learned years later. “She held me up and a policeman named Thomas Penn got me out and passed me to a 17-year-old girl. I didn’t find out what happened until I was 20.”

Alf had for years been on a lifelong mission to get a memorial to those who died and was to go on to establish the fundraising charity in 2006 with Sandra Scotting, a relative of a victim who is secretary of the memorial trust.

Henrietta Keeper was at the top of the stairway with a friend when she felt uneasy about the surging crowds and changed her mind. The 15-year-old turned back and went to join her mother in the railway arches shelter by the Salmon & Ball pub instead—a decision that saved her life, but not her friend’s.

“Dolly Warrington begged me to come down shelter,” she recalls. “But I was frightened. Dolly went down and was killed in the crush.”

Henrietta, now 90, survived with haunting memories of the dead that have remained with her for life.

“I saw the bodies lined up outside the pub,” she remembers. “Their insides and organs were coming out of their mouths from being crushed to death. I remember seeing a little dead boy with his organs hanging out and will always remember that.”

Another survivor at the unveiling was Reg Butler, now 83, was heading to the shelter with his dad from their home in Old Ford Road when violent vibrations from by anti-aircraft guns being tested in Victoria Park caused him to trip in the road. Those few seconds’ delay caused him to miss the death crush on the stairway just in time.

The tragedy wiped out whole families, sometimes three generations seeking shelter together from an enemy air-raid that ironically never came.

Among them was the brother and baby sister from Maidstone staying with relatives in Bethnal Green and killed with them in the shelter. Little Kenneth Sharp, 5, and 16-month-old Irene, were caught in the crush with their aunt Olive Thorpe, 36, and cousins Marie, 12, and baby Barbara, 2.

Six members of the Mead family were killed, George and Florence Mead, and their children, George Jnr, 12, Kenny, 10, Maureen, 4, and granny Eliza Mead, 67, and their newly-married daughter Matilda Korobenick, 33.

Annie Ellam, 44, died with her three children, Frances, 20, Rosina, 17, and baby Pauline, 2½.

Two more babies were crushed in the carnage, Iris Clatworthy, 2, and the youngest of all, Robert Yeaman, just a year old.

Louisa Hoye, 44, died with her three daughters, Rose, 19, Lilian, 13, and Marjorie, 7.

Ted and Bessie Roche, 40 and 42, died with their children Joan, 9, and Eddie, 8.

Elizabeth Quorn, 43, died with her children William, 14, and Gwendoline, 5.

Pensioners Florence and Thomas Letchmere, both 66, died with their son Thomas, 48, who went back to try to save them.

Nine neighbours including two children were found dead together, Edith Bosworth, 50, and daughter Irene, 17, Lilian Chandler, 35, and daughter Doreen, 14, Mary Hall, 47, and daughter Irene, 8, Florence Vanner, 49, Sarah Jolly, 51, and Peter Johns, 7.

Also among the dead was professional boxer Richard Colman, 34, who fought under the name Dick Corbet.

The long-awaited Stairway to Heaven memorial finally unveiled yesterday, the name taken from an East London Advertiser headline in 2006 when plans for a memorial were first announced, bears 173 names and pinhole spots of daylight peering through the canopy, one for each of the men, women and children who perished that night.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here